Simone Capocasa, Israele antico e l’eredità della monarchia davidica. Prefazione di Maria Giovanna Biga (Monografie di Horti Hesperidum, 16), Roma 2024.

Il processo di formazione che ha portato alla definizione del popolo ebraico è uno sviluppo determinatosi progressivamente nel tempo attraverso il passaggio da una fase di genesi, fino alla progressiva costituzione di uno Stato di tipo nuovo, nel quale è impossibile escludere il contributo apportato dalla dialettica con le popolazioni cananee limitrofe. Il passaggio dal fluido periodo dei Giudici alla monarchia unita, sarà caratterizzato dall’elaborazione di un programma politico e da una riforma religiosa senza precedenti. Davide, ed in seguito Salomone, furono gli emblemi di quelle rilevanti personalità che, avvalendosi delle propizie condizioni, plasmano la storia creando un diverso modello di riferimento. La nascita della dinastia davidica costituì, dunque, un momento di svolta decisivo nel quale la continuità con il passato si fuse con un inizio completamente nuovo, la genesi di un’epoca che terminerà soltanto con la distruzione del Tempio.

Simone Capocasa, nato a Roma nel 1975, curatore Archeologo della Sovrintendenza Capitolina, titolare di un Dottorato di ricerca in Archeologia, conseguito all’Università degli studi di “Tor Vergata”. Per Horti Hesperidum ha già pubblicato un saggio e diversi articoli inerenti il collezionismo e la diffusione della cultura archeologica orientale.

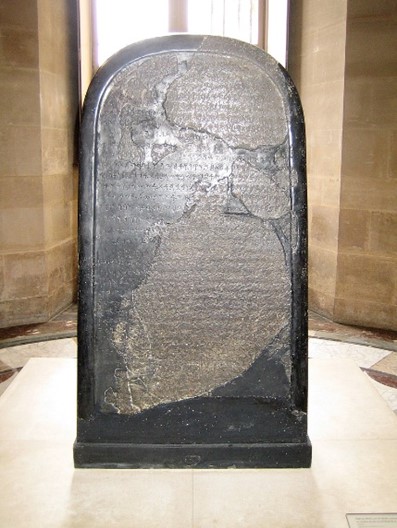

Questo saggio nasce da un’approfondita rilettura dell’Antico Testamento considerato una fonte di preziose informazioni storiche e dall’analisi di un gran numero di documenti, oltre che dallo studio di tutte le testimonianze archeologiche attualmente in nostro possesso.

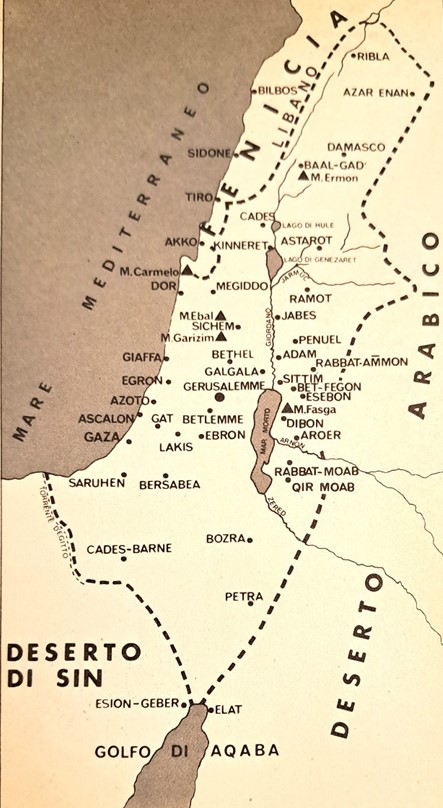

Il processo di formazione che ha condotto alla costituzione dello Stato di Israele deve essere considerato imprescindibile dall’apporto culturale delle popolazioni palestinesi locali e in particolare dal substrato cananeo, il quale è stato fondamentale per le successive vicende storiche. L’arco cronologico considerato prende avvio dal periodo dei Giudici giungendo fino al ritorno degli esuli babilonesi, comprendendo vari excursus che trattano dei momenti più salienti della storia di Israele, arrivando sino a descrivere la figura di Gesù.

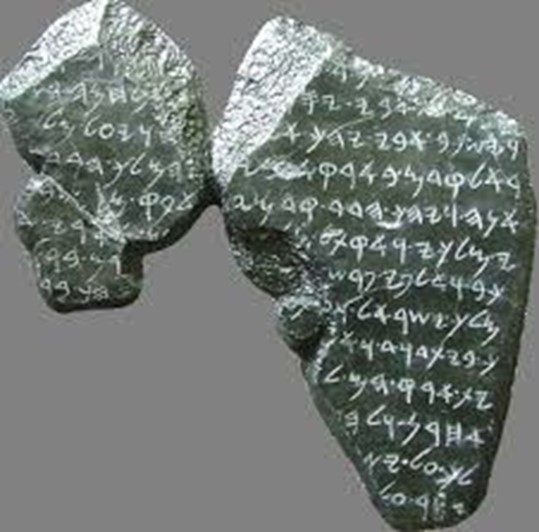

Tema centrale di questo studio è la realizzazione, attraverso precise condizioni, di un’eredità storico-culturale-religiosa che solo in un determinato contesto e solo in uno specifico tempo potevano compiersi, ovvero durante il regno della dinastia davidica. La realtà storica dei due esponenti più rappresentativi della cultura israelitica è suffragata oltre che dalle evidenze archeologiche anche dall’essere stati artefici, oltre che di una pianificazione edilizia su grande scala, soprattutto di un ambizioso programma politico e di una riforma religiosa molto lontana dal culto monoteistico sviluppatosi nell’ultima fase del periodo monarchico.

L’epoca della formazione dell’entità politica monarchica diventa nelle sue stesse tradizioni storiografiche il periodo di collocazione di tutte le storie dotate di valore fondante. Non è perciò un caso che la storiografia d’Israele abbia avuto inizio soltanto al tempo di Davide. Si tratta, in sostanza, di una scelta politica in rapporto alle difficoltà di costruire uno Stato unitario su una base frammentata e diversificata. L’intelligenza di tale metodo di governo era nell’affermazione di Yahveh come divinità nazionale e dinastica, parallelamente alla tolleranza verso altri culti che continuarono ad essere praticati soprattutto in ambito agreste.

La preferenza per Yahveh, presumibilmente dio d’ambiente nomadico-pastorale originario del Sinai, può essere considerata sotto l’aspetto di un’attenta valutazione politica, in quanto non essendo una delle divinità maggiori non era legata ad ambienti politico-religiosi radicati.

Non è facile stabilire fino a che punto fosse giunta al tempo di Davide la fusione tra la religione yahwista con i culti cananei. Probabilmente si assiste già allora ad una sorta di sincretismo con i culti delle città-stato siro-palestinesi ed in particolar modo fenicie, nelle quali l’ideologia regale era strettamente connessa alla divinità.

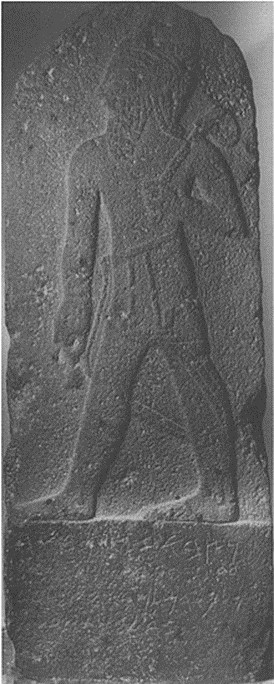

Al tempo di Salomone venne elaborata quella che è stata definita la «teologia reale di Sion», per cui Yahveh aveva eletto Gerusalemme a sede unica del suo culto e la dinastia davidica come suo garante. In base a questo patto con la monarchia, Gerusalemme diveniva da un lato l’eterno centro yahwista e la casa di Davide, l’istituzione consacrata e celebrata come l’unica mediatrice tra il Signore e il suo popolo. Il sovrano, pertanto, diviene il sommo sacerdote regio, titolo fatto derivare direttamente dall’età patriarcale, che siede sul trono del Palazzo reale come il Signore presiede nell’Assemblea divina. Yahveh non è ancora la divinità assoluta nella quale verrà trasformato in seguito, in effetti era inserito in una struttura enoteistica, per tal motivo sembra del tutto naturale fosse affiancato ad una paredra femminile, Ashera, come dimostrano le indicazioni derivanti dalle attestazioni epigrafiche. Questo è il momento nel quale presumibilmente si assiste alla legittimazione della trascendenza del re, emanazione ipostatica del Signore attraverso l’acquisizione di qualità e attributi divini sacri, ovvero come suo figlio.

In questo paradigma regale i sovrani come Hiram e Salomone, melki delle rispettive città sante, erano verosimilmente considerati esseri trascendenti, un’emanazione della sapienza e giustizia di Baal/Yahveh.

Queste sono le prerogative con le quali la cultura levantina si manifestò ai Greci durante i primi contatti commerciali avvenuti nel Mediterraneo orientale nell’ultima fase precoloniale. Tuttavia, è nel periodo di maggior espansione delle rotte marittime che avviene l’elaborazione in ambiente ellenico della rappresentazione del sovrano/Melqart, il quale nel suo cammino verso ponente, imitando il percorso dell’eclittica solare, si spoglierà della sua veste regale per essere associato ad Herakles.

Gli eventi successivi modificheranno l’assetto politico della fascia siro-palestinese. Alla divisione del regno unito ed alla perdita d’indipendenza del regno d’Israele a causa dell’invasione assira, si contrappone la sopravvivenza del territorio di Giuda nel quale si avvia una decisa evoluzione del sistema teologico e cultuale, allo scopo di fronteggiare i cambiamenti politici internazionali. Questo processo si manifesta con l’introduzione di un regime monoteistico, il quale ebbe tappe fondamentali nelle riforme religiose di Ezechia e Giosia (VII sec. a.C.). Per la prima volta si concepisce il disegno di un regno che venera un solo dio in un solo luogo e nel quale non è più unicamente la legittimità e il valore del re a determinare l’atteggiamento della divinità, ma il comportamento dell’intero popolo di devoti: segno che il prestigio della regalità si era molto affievolito rispetto all’incarnazione divina del sovrano del periodo salomonico.

Questo aspetto si accentuerà soprattutto in seguito nella comunità post-esilica, per la quale la fede religiosa era il principale elemento di coesione nazionale dopo la scomparsa delle strutture politiche di riferimento. I riformatori religiosi del VI-IV sec. a.C. riuscirono a sottrarsi alla deculturazione insita nella deportazione, tramutando l’esilio babilonese nello stimolo per edificare la coscienza nazionale, nel tentativo di recuperare un’identità storica, riempiendo di valori simbolici la religione ebraica e trasformandola in una realtà completamente diversa da quella che era stata nel passato, in particolare nel periodo davidico.

I successivi periodi, quello persiano e quello ellenistico, costituiscono i momenti che condurranno ad importanti trasposizioni analogiche, ad identificazioni universalistiche e interpretazioni astrologiche tra i diversi culti delle differenti religioni che vennero ad incontrarsi o affrontarsi in questi periodi storici; la più gravida di conseguenze è quella che preparò il terreno alla storia della morte e resurrezione del Cristo.

I fondatori della dinastia davidica sono gli emblemi di quelle rilevanti personalità che avvalendosi delle propizie condizioni plasmano la storia creando un diverso modello di riferimento. Un momento di svolta decisivo nel quale la continuità con il passato si fonde con un inizio completamente nuovo, la genesi di un’epoca che terminerà soltanto con la secessione dalla corona e in seguito con la distruzione del Tempio.

Il disegno politico di Davide, ereditato da Salomone, è stato caratterizzato dalla comprensione della necessità di creare un regno in un contesto multiculturale, tramite la tolleranza e l’inclusione. Lezione che né le generazioni successive al sovrano né, tantomeno, il mondo moderno, hanno saputo comprendere.

English version

This essay arises from an in-depth rereading of the Old Testament considered a source of precious historical information and from the analysis of a large number of documents, as well as from the study of all the archaeological evidence currently in our possession.

The formation process that led to the establishment of the State of Israel must be considered essential from the cultural contribution of the local Palestinian populations and in particular from the Canaanite substratum, which was fundamental for subsequent historical events. The chronological period considered starts from the period of the Judges up to the return of the Babylonian exiles, including various excursus that deal with the most salient moments in the history of Israel, going as far as describing the figure of Jesus.

The central theme of this study is the creation, through precise conditions, of a historical-cultural-religious legacy that could only be fulfilled in a specific context and only in a specific time, during the reign of the Davidic dynasty. The historical reality of the two most representative exponents of Israelite culture is supported not only by archaeological evidence but also by the fact that they were the architects, as well as large-scale building planning, above all of an ambitious political program and a religious reform that was very far from the monotheistic cult that developed in the last phase of the monarchic period.

The epoch of the formation of the monarchical political entity becomes in its own historiographical traditions the period of collocation of all stories with founding value. It is therefore no coincidence that the historiography of Israel began only in the time of David. It is, essentially, a political choice in relation to the difficulties of building a unitary state on a fragmented and diversified basis. The intelligence of this method of government was in the affirmation of Yahveh as a national and dynastic divinity, in parallel with the tolerance towards other cults which continued to be practiced especially in rural areas.

The affection for Yahveh, presumably god of the nomadic-pastoral environment originating from Sinai, can be considered from the aspect of a careful political evaluation, since not being one of the major deities he was not linked to rooted political-religious environments.

It is not easy to establish the extent to which the fusion between the Yahwist religion and the Canaanite cults had reached the time of David. We were probably already witnessing a sort of syncretism with the cults of the Syro-Palestinian and particularly Phoenician city-states, in which the royal ideology was closely connected to divinity.

At the time of Solomon, was developed what was defined as the «royal theology of Zion», whereby Yahweh had elected Jerusalem as the sole seat of his cult and the Davidic dynasty as its guarantor. On the basis of this pact with the monarchy, Jerusalem became on the one hand the eternal Yahwist center and the house of David, the institution consecrated and celebrated as the only mediator between the Lord and his people. The sovereign, therefore, becomes the royal high priest, a title derived directly from the patriarchal age, who sits on the throne of the Royal Palace as the Lord presides in the divine Assembly. Yahveh is not yet the absolute divinity into which he will be transformed later, in fact he was inserted in a henotheistic structure, for this reason it seems completely natural that he was placed alongside a female paredra, Ashera, as demonstrated by the indications deriving from the epigraphic attestations. This is the moment in which we potentially witness the legitimation of the king’s transcendence, hypostatic emanation of the Lord through the acquisition of sacred divine qualities and attributes, or as his son.

In this royal paradigm, rulers such as Hiram and Solomon, melki of their respective holy cities, were likely considered transcendent beings, an emanation of the wisdom and justice of Baal/Yahveh.

These are the prerogatives with which the Levantine culture manifested itself to the Greeks during the first commercial contacts that occurred in the eastern Mediterranean in the last pre-colonial phase.

However, it is in the period of greatest expansion of the maritime routes that the representation of sovereign/Melqart, was developed in the Hellenic environment, who on his way towards the west, imitating the path of the solar ecliptic, will take off his robe regal to be associated with Herakles.

Subsequent events will change the political structure of the Syrian-Palestinian belt. The loss of independence of the kingdom of Israel due to the Assyrian invasion is contrasted with the survival of the territory of Judah, in which a decisive evolution of the theological and cultic system begins, with the aim of facing international political changes. This process manifests itself with the introduction of a monotheistic regime, which had fundamental phases in the religious reforms of Hezekiah and Josiah (7th century BC). For the first time the plan of a kingdom conceived that veneration of a single god in a single place and in which it is no longer solely the legitimacy and value of the king that determines the attitude of the divinity, but the behavior of the entire people of devotees: a sign that the prestige of royalty had weakened greatly compared to the divine incarnation of the sovereign of the Solomonic period.

This aspect will be accentuated above all later in the post-exilic community, for which religious faith was the main element of national cohesion after the disappearance of the political structures of reference. The religious reformers of the 6th-4th centuries B.C. managed to escape the deculturation inherent in the deportation, transforming the Babylonian exile into a stimulus to build national consciousness, in an attempt to recover a historical identity, filling the Jewish religion with symbolic values and transforming it into a completely different reality from what it had been in the past, particularly in the Davidic period.

The subsequent periods, the Persian and the Hellenistic, constitute the moments that will lead to important analogical transpositions, universalistic identifications and astrological interpretations between the different cults of the different religions that came to meet or face each other in these historical periods; the most pregnant with consequences is the one that prepared the ground for the story of the death and resurrection of Christ.

The founders of the dynasty are the emblems of those relevant personalities who, making use of favorable conditions, shape history by creating a different reference model. A decisive turning point in which continuity with the past merges with a completely new beginning, the genesis of an era that will end only with the secession from the crown and subsequently with the destruction of the Temple.

David’s political plan, inherited from Solomon, was characterized by the understanding of the need to create a kingdom in a multicultural context, through tolerance and inclusion. A lesson that neither the generations following the sovereign nor, much less, the modern world, have been able to understand.